Cédric Breisacher—Toward a zero-waste workshop

The multi-talented artist, woodworker, sculptor, researcher and creator of the biomaterial Agglomera welcomes us to his workshop for a fascinating in-depth conversation around his passions

Version Française (originale)→

After your industrial design training and several years of work experience, you went back to study at ENSCI to deepen your theoretical knowledge, especially on the waste management issues. What impact did these studies have on your work?

After my master’s degree in design engineering at ISD Valenciennes, I developed a passion for model making despite limited facilities. It was during my internship with Valentin Loellmann that I discovered woodworking. My training was primarily methodological, with a noticeable gap in theoretical knowledge, particularly regarding major design thinkers like Bruno Munari, Andrea Branzi, and William Morris.

I created my workshop with the aim of producing solid wood objects locally, sourcing materials from northern France. My goal: to create sustainable and environmentally responsible objects. Faced with an accumulation of wood shavings, I first implemented a recovery system, then decided to return to studies at ENSI to deepen my research and develop new methodologies.

After your time at CoFabrik in Lille, you moved to JAD in Paris, another shared workshop. Beyond the practical advantages like sharing stationary machines, what do these shared spaces offer you compared to an independent workshop?

The main advantage is clearly working together rather than being alone in your workshop — your “cave” — and being able to interact daily with people from our field and other disciplines. This creates a different daily routine and rhythm. There’s a unique energy that flows in a shared workshop, but I’ve always worked in spaces that included private studios, which allows me to isolate myself when I need to.

What’s special about the JAD workshop is its administrative and cultural team that brings the space to life and organizes professional events. We meet interior architects, curators, and we’re encouraged to present our work in 10-minute formats. These oral presentation exercises become valuable during trade shows or conferences.

It’s a dynamic place that goes beyond our individual work. We’re encouraged to collaborate with each other, which enables different practices to meet, knowledge to be shared, and creates unexpected bridges between design and craftsmanship.

In your thesis defense, you talk about relational objects and define the emotional connection between humans and material objects. As a designer-sculptor, do you think you can influence the relationship that buyers have with your creations?

I think so, because when a collector or someone buys one of my pieces, it’s often through an emotional connection that forms at first sight. The buyers are usually already in love with the work, or fall for the lines, the curves, or the story I tell through the objects. It’s funny, for example, when I gave a stool like this one to my girlfriend, she spent the whole evening holding it in her arms. There’s an energy that I transmit to my objects, particularly through the gouge work, which creates a very visceral relationship with the material — everything is worked by hand, everything is done with affection. This gouge work, as you can see behind you, establishes a direct relationship with the material and necessarily creates a symbiosis between the creator, the creation of the piece, and the material. The final piece thus becomes the synthesis of all this methodology and approach.

Still on this subject, can you tell us about your relationship with the tools and how it influences your practice and style?

There have been two phases in my practice. In the beginning, I started with an angle grinder equipped with an Arbortech disc, the classic sculptor’s tool. This tool allows you to rough out the wood without guides or references. It’s truly the body’s gesture that gets imprinted in the wood. I began by sculpting platforms like this one, where the tool, an extension of the arm and hand, becomes inscribed in the wood’s forms. The tool reacts differently depending on the wood’s density: when encountering a knot, it merely skims the surface, while in softer areas, it cuts deeper at once. I seek to develop this dialogue between material and human, where the tool acts as a mediator between the two. The tool becomes this essential link between the wood’s surface and my hand. Like a microphone, it enables a true dialogue between the material and my gesture.

“The gouge is truly a tool that allows you to understand the material and establish an equal relationship with it. I have my direction, the wood has its own, and from this confrontation emerges a harmonious balance.”

Do you have a tool that you feel particularly attached to, that guides your way of working?

This is the second part of my evolution in manual work. In the beginning, I only used electric tools — it was kind of the easy solution. Electric tools don’t take into account the wood grain; you can carve even against the grain. Then gradually, I reintegrated manual cutting tools, which force us to respect the direction of the grain and the material. You have to listen to it, look at it, work with it and not against it.

Sometimes, it’s the material itself that gives birth to a form: you encounter a knot, you rework it with the gouge, you work with the opposing grain, you hollow it out, and a form naturally emerges. As soon as the trace of the gesture is beautiful, I stop and the piece is set. That’s why in my latest creations, particularly the “Intuitive Archaism” collection, gouge work becomes crucial. After roughing out with the grinder, all the final forms are defined by gouge work.

The gouge is truly a tool that allows you to understand the material and establish an equal relationship with it. I have my direction, the wood has its own, and from this confrontation emerges a harmonious balance.

What made you choose wood as your preferred material? Did you first have the desire to work with this material before starting, or did you begin with industrial design before discovering wood?

Wood has always been a part of my life. In my family, we are forest owners. Every winter at Christmas, we would go for walks in my grandfather’s forest. Wood has always been present, even if I only realized it later. I really started to discover this material during an internship with Valentin Loellmann, a designer, sculptor, and artist based in Maastricht. He works primarily with wood, but also with metal. I already had a special affection for this material — during my studies, I drew many turned wood objects…

For me, wood represents the quintessential material for renewable and sustainable objects. When I opened my workshop, I wanted to work with a local material, and the proximity of the forest near Lille reinforced this choice. Once you start working with wood, it’s difficult to let it go.

Your work oscillates between functional furniture and sculptural artwork. Is this a deliberate choice to blend these two worlds, to infuse art into everyday objects, or rather a desire to maintain a presence in each of these domains?

In fact, there’s a very porous boundary between art and design today. I’m not particularly trying to fit into a specific category. It’s more my work process that defines this approach: I don’t use any templates, so each piece is unique since every piece of wood is different. I can’t reproduce objects identically, especially since my practice increasingly incorporates sculptural elements. This uniqueness is intentional — I want to create objects that are always different and stimulating to make. Mass production seems too repetitive and doesn’t align with my working method. This porosity between disciplines is actually crucial today. We’re fortunate to live in an era where we can question these traditional boundaries. These objects, situated at the intersection of art and design, allow us to explore more theoretical concepts, to create manifesto pieces that question our ways of living and our relationship with objects. This approach paves the way for research and allows us to present creations that aren’t typically found in conventional retail.

Let’s go back to what you were explaining about the continuity between muscle, gesture, tool, and your intuitive and instinctive way of working. Can you describe this state, somewhat like Jackson Pollock entering a kind of trance?

Yes, it’s quite similar. When I spend more than an hour sculpting, there comes a moment when I forget myself. It’s the same on the wood lathe — you forget everything around you and become totally focused on the present moment, on the gesture. It’s like a choreography. For me, the movement is felt right down to my toes. It’s really like dancing: when I start a sculpture from the left, the gesture moves to the right, the shoulders turn, the hips follow, and sometimes I even find myself on my tiptoes. It’s a real pleasure, purely instinctive. There’s intuition, osmosis, euphoria — while remaining controlled, of course, because you have to respect safety gestures. These precautions are an integral part of my sculpting choreography.

The challenge is knowing when to stop. You could sculpt endlessly for hours, but there’s always a moment when, naturally, a balance is created in the whole.

Whether it’s muscle fatigue or the relationship between forms, I can sense when I no longer need to sculpt. The piece reaches another state, like a new form of life. I then take it out of the workshop, let it live in the space, observe how it catches the light. If certain aspects of its forms displease me, I make slight adjustments to achieve perfect harmony.

Can you tell us about your residency last year in Sweden as part of the MIRA program, and what you learned about Scandinavian craftsmanship and design?

I completed this residency with Marion Gouez, a textile designer specializing in patterns for major brands, as part of the Végétamorphe project (PRIC Program—Collaborative Innovation Research Project at JAD). Our collaboration aimed to draw inspiration from living things to create innovative technical processes. We began by developing a jacquard fabric, creating four-handed patterns that represented tree bark. Our approach was very instinctive: we first created a background with wood shavings soaked in ink, then gradually added moss and lichen details using chalk and paint.

The pattern evolved like a photographic focus adjustment, moving from blur to sharp, creating different layers of interpretation. The MIRA residency in Sweden allowed us to deepen this approach. During our 20-day journey from Abisko to Hurtrask, we immersed ourselves in pine forests and frozen Nordic landscapes.

Inspired by Soetsu Yanagi’s philosophy on the interpretation of living things in Japanese craftsmanship, we developed an approach where technical gesture translates natural essence. This reflection, combined with meeting a local craftsman specializing in bent wood, led us to create the ‘bra’ chair. This piece marks a turning point in our work: rather than sculpting nature, we create reproducible objects that capture its very essence.

Let’s talk about your commitment to circular production in your workshop, particularly through your latest Not Wasted series. Can you describe the concept behind this series and your efforts to popularize Agglomera?

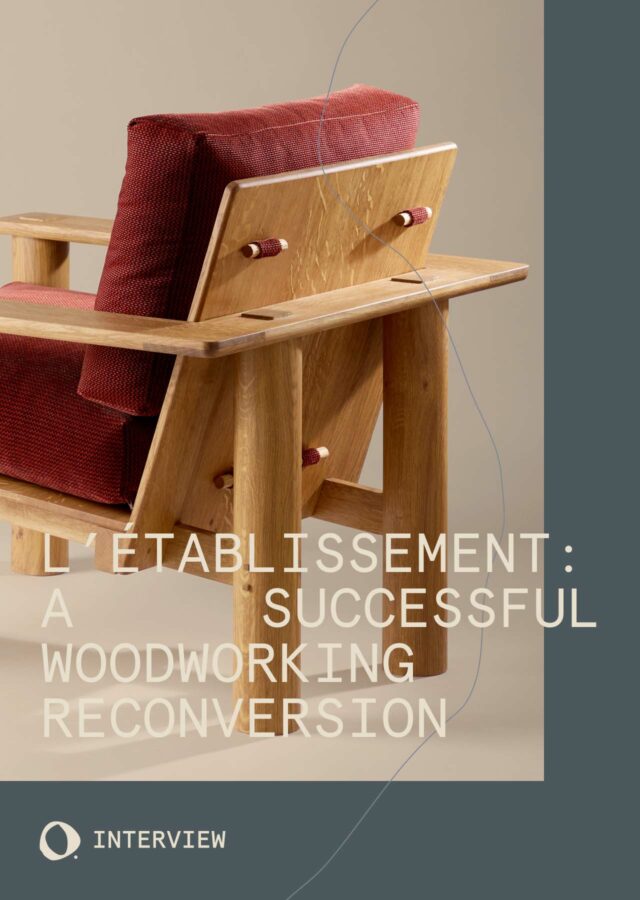

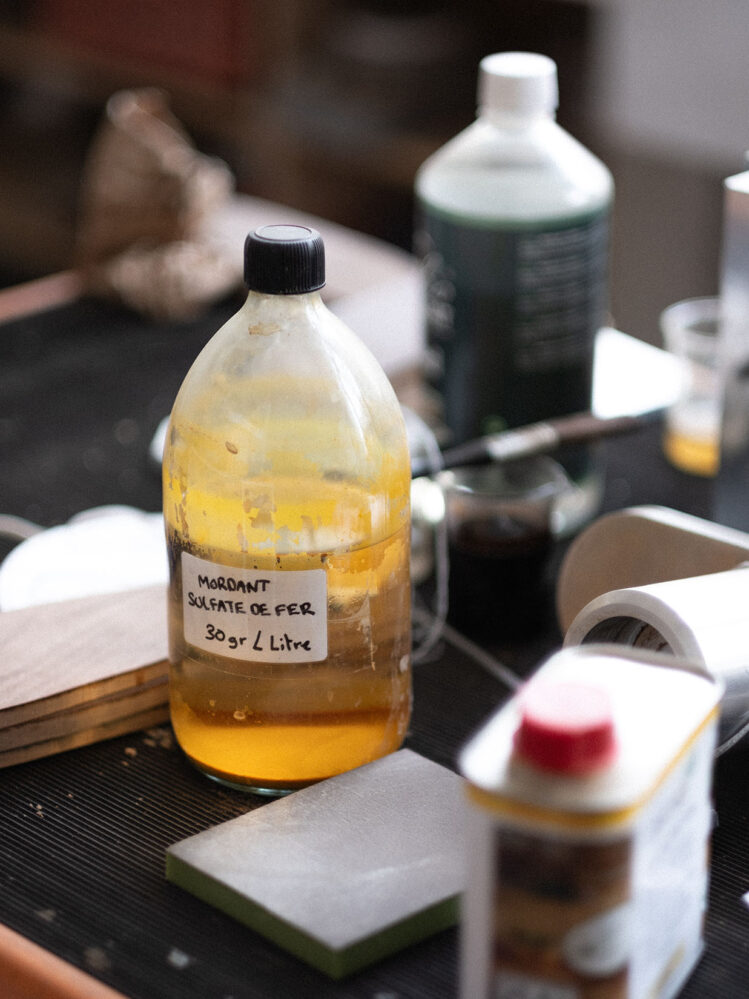

Agglomera is a material I developed during my master’s at ENSCI. It’s a mixture of wood shavings, potato starch, and water — starch (amidon).

It’s an organic adhesive that I continue to develop to bind wood shavings and create a new material that allows me to reclaim and recycle my production waste. The concept behind this material is to transform my workshop into a zero-waste space. That’s actually the origin of the name Not Wasted. This material has several advantages: it can be compressed into plates in molds, but also modeled, thus allowing for an additive rather than subtractive practice. In the Not Wasted chair, I combine both approaches: the solid wood base, through its subtractive sculpting, generates exactly the amount of waste needed to create the agglomerated seat. The design is modular: the three bases, depending on their arrangement, can create different forms, and it’s the modeling technique that defines the final function, such as that of the chair. This is the first concept of the Not Wasted series. The second concept aims to represent the idea of the cycle, particularly in the series of side tables and lamps. In these pieces, I combine wood in three different states of its life cycle, allowing users to see the material in its natural, crafted, and recycled states, thus awakening ecological awareness.

You mentioned trying to popularize this through an open source publication?

I haven’t published my research yet, so the recipe isn’t available on my website. However, I’m democratizing the research through workshops and training sessions — I do about 3 or 4 per year. I’m now being asked to lead these Agglomera workshops, where I share this starch recipe. These workshops are always very successful because participants realize they can use many materials they already have at home. It’s a recipe I chose not to patent because I believe it belongs to the commons, given how simple it is to implement: water, potato starch, and you get glue. I also use other additives like glycerol, oil, vinegar, depending on the properties needed for the material, and I share this knowledge during my workshops. Even though these sessions are often too short to delve deep into the development of bio-based materials, what’s essential is the approach and practice of creating an accessible glue for everyone using available waste. For me, that’s where the democratic aspect currently lies.

And the second ambition is to create with Agglomera a publishing house that mass-produces molded objects, mainly to create an economy linked to waste and to add value to a resource present in my workshop.

How would you define your style and what do you think about the attribution of style for artists and creators like yourself?

I don’t really know how to answer this question. I tend to think “well, we’ll see when I’m dead” what style they’ll attribute to me. For now, I don’t really worry about it too much. There are certain words that keep coming up, like “organic.” I used to define myself as minimalist, but now, even though I greatly appreciate minimalism, I find that it doesn’t really reflect my practice.

We can observe a movement that has developed over the past decade or so, particularly in the Netherlands and Belgium. In France, we have more difficulty establishing this movement. We are more oriented toward design linked to fashion, rather than design where creators champion technical innovation.

In terms of movement, I feel closer to the Dutch approach, where we really work with the material and develop unique processes. And for style, it’s clearly organic, even biomorphic…

Sensory too, perhaps? Yes, that’s it — organic and sensory, that fits well.

What is the future for Cédric Breisacher? In the medium term, what are your upcoming activities, and in the long term, in 10 years?

Good question! I can only see three years ahead — just kidding! In the medium term, there are several exhibitions. 2025 is going to be quite busy: the Émergences Biennial in April, Collectible Fair in March with Lune Gallery, the Amour Vivant Biennial in autumn, and an exhibition with Objects with Narratives in April too, I believe. And probably participation in Paris Design Week, but I haven’t applied yet. So those are the very short-term exhibitions. Regarding development, my tenure at JAD ends in 2026, in a year and a half. I’ll need to change workshops.

This workshop change will likely take place in Brittany, where I plan to continue working in a collective space — and maybe even create it with another designer friend, Frédéric Saulou. We’re going to partner up to have a permanent workshop where I can settle for the long term and have space to undertake even more ambitious sculpture projects. In three years, I’ll also be self-sufficient in wood, as we’ve just taken over my grandfather’s forest management. We did some logging this winter, so I should have wood to work with in three years. This means establishing my own material and resource circuit. This autonomy and these woods, rich with history, might allow me to focus more on sculptural pieces for the exhibition and gallery market, where I really want to develop sculpture on a larger scale. In parallel, I want to develop the Agglomera laboratory to commercialize a first series of objects. In ten years, the goal is to have an Agglomera workshop separate from the wood fabrication workshop.

Looking forward to following all of this! Finally, what advice would you give to the 10-year-old Cédric Breisacher?

Ah, I like this question! To 10-year-old Cédric, that little boy who ran everywhere and didn’t listen in class, I would tell him to trust himself and that everything will be fine. It’s okay if you don’t think like others — it’s actually an advantage and a strength. Don’t see your difference as something that marginalizes you, but rather as what makes you unique and singular. You have the right to be different.